Tbilisi’s unique charm is largely shaped by the beautiful Buildings in the city center. Most of that Buildings were built in the 19th century or the early 20th century. When an independent researcher or simply a curious passerby tries to understand who built these Buildings and how, they will overwhelmingly find an Armenian trace.

The Armenians not only formed the majority population in Tbilisi during that period, but were also active entrepreneurs and businessmen. Following the discovery of oil fields in Baku, they began purchasing land, exploring those areas, finding oil deposits, and exploiting them. This brought significant wealth to Armenian businessmen from Tiflis. And since many of them were European-educated and had refined taste, they started building their homes, hotels, caravanserais and other Buildings in Tiflis with the highest standards of elegance. The Buildings were usually designed either by Armenian architects or by renowned professionals invited from Italy. They used the finest Venetian ceramics and furnished their homes with luxurious furniture.

They also generously donated to the city of Tbilisi with their earned wealth—building bridges, hospitals, and universities.

After the establishment of the Soviet regime, these wealthy, tasteful, and philanthropic Armenians were either exiled from the country with their families or given a tiny room in the basements of the very buildings they had once owned—where many of them died in poverty and hunger. Some of them don’t even have graves.

However, the magnificent buildings they constructed were repurposed to house many ordinary families, whose descendants still live in them today. Many of these residents have heard and preserved the stories of the Buildings’ original Armenian owners from their parents. Meanwhile, descendants of many of these wealthy Armenians, now living in European countries, continue to assert that they have preserved the ownership documents of these ancestral properties.

This publication highlights a few Buildings in Tbilisi’s center built by prominent and wealthy Armenians. Of course, it doesn’t cover the full extent of the vast architectural heritage left by Armenians in the city—only a small portion. Additional stories of Armenian-built Buildings in Tbilisi can be found in the map attached to this article.

The Woman Behind the Building: Evelina Ter-Akopova

In the Sololaki district of Tbilisi—at the corner of present-day Tabidze and Asatiani streets, No. 21/24, two facing Buildings stand out till now. One of them is covered with dozens of sculpted faces sticking out their tongues. The Art Historian Inna Gyodakyan told us the story she gained: those tongues were aimed at the lady of the house across the street—an Armenian woman named Evelina Ter-Akopova.

“Evelina Ter-Akopova invited architect-designers from Italy and built a magnificent mansion. Her neighbor across the street grew envious and declared she would build an even better one. Evelina laughed, saying it would be impossible. The neighbor ended up spending twice as much and built a house twice as large, then covered it with sculptures of faces sticking out their tongues in all directions—as if to say to Evelina: ‘See? I did it.’ The neighbor even said: ‘Every time I look out my window, I’ll admire your beautiful house and enjoy its aesthetics, while you will have to look at the tongues I’m sticking out at you,” told the story of the mansion the art historian Inna Gyodakyan.

Evelina Beglyarovna Ter-Akopova was far from an ordinary woman–Inna Gyodakyan said: “She was not only the wife of native Armenian of Tbilisi Gerasim Nikitich Ter-Akopov—a first-guild merchant and oil producer from the Baku oil fields—but she also was an oil extractor and refinery owner in her own right, heading a separate company. Evelina also owned sawmills, wood-cutting factories on Madatov Island in the river Kura. The couple had their own stock exchanges”, she said.

The July 15, 1890 issue of the Kaspi newspaper in Baku published a complete list of oil companies operating on the Absheron Peninsula, she noted, stating that Gerasim was engaged in drilling, while Evelina was involved in both drilling and oil extraction.

Inna Gyodakyan said that Evelina’s name also appears—along with other well-known and wealthy Armenians—in the 1911 list of candidates for the Tbilisi City Council elections. “Only property owners who had made large donations to the city budget were eligible to vote. Women’s names on such lists were rare”, she told.

Evelina built the mansion in 1896—a date engraved on the building’s faցade– after her husband’s death. The current residents of the building, told Inna, that Evelina used to live in the section of the house where her name is engraved on the stone carpet in front of the entrance. “Other two entrances of the building were rented out—constructing income-generating houses was a common practice in Tbilisi at the time”, she said.

One of the residents even assured Inna that his mother personally knew Evelina, who had lived on the second floor and remained there until old age—almost reaching 100 years.

Evelina’s black marble bust is mounted on the pink facade of the house. Inside, there are white marble staircases and ornate wrought iron railings.

“Even after the Soviet expropriation of property from the wealthy, Evelina continued to live in her homе. Тhough the building was nationalized and repopulated with various families”, Inna Gyodakyan said.

A third floor has now been added to the top of the Buildings, and the pink mansion is wrapped in a web of black electrical wires that run across its facade. ” Yet even in this state, it’s not hard to grasp the envy and sense of comparison Evelina Ter-Akopova’s neighbor must have felt—looking at the pink design crafted by an Italian architect”, the art historian said.

The Poet’s Home, the City’s Memory: Armenian Story Behind 18 Amaghleba Building

Although Elena Kolesnikova, a scientist biologist at the Tbilisi Botanical Garden, is extremely busy with her work, she makes her way to 18 Amaghleba Street at least once a week. The 72-year-old woman opens one of the double doors with trembling hands, on the glass windows of which there is an ornamental metal frame—with two letters written on it: I and Sh.

Then, with swaying steps, she walks forward on tiles nearly 200 years old, holds onto the carved wooden handrail of the same age, and climbs to the third floor. The metal door is always open for her. Her grandfather’s family lived in this house: the family of Hovhannes Tumanyan, one of the greatest Armenian writers, poets, and public figures.

And the three-story Buildings adorned with decorative carvings, where the writer’s family had been invited to live, was built in the second half of the 19th century by Tbilisi-born wealthy Armenian, Georgian state and cultural figure Iosif (Hovsep) Shanshyan, the son of the member of the Tbilisi Parliament Grigor Shanshyan —his initials are still preserved on the canopy of the entrance and in the ornamental metalwork of the entrance doors.

“Who hasn’t sat around this small table? Aghayan and Komitas, Leo and Shirvanzade, Marr and Zhivelegov, Shant and Siamanto, Isahakyan and Papazyan, Hovhannisyan and Tsaturyan, Bryusov, Gorodetsky, Iashvili, Tabidze, Grishashvili, and many, many others,” told us Tumanyan’s great-granddaughter, who had heard many of these stories from her mother, Nadezhda, who in turn had heard them from her father, Mushegh—Tumanyan’s eldest son and one of his ten children.

She recounted stories of long discussions and debates that Hovhannes Tumanyan had with one of the key figures of the Armenian national liberation movement—General Andranik and the renowned poet Vahan Terian.

“Vahan Terian was pro-European; he believed that the salvation of the Armenian people should be sought in Europe. Meanwhile, General Andranik insisted that it could only be found through the united strength of the Armenian people,” said Elena Kolesnikova. “Tumanyan would argue with Terian for hours—they held completely opposing views and, in the end, each stood by his own. In the case of Andranik, however, although they debated, they would eventually reach common ground.”

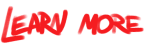

Valery Bryusov, having graduated from the Armenian Lazaryan Seminary of Oriental Languages in Moscow, was fluent in both Classical Armenian (Grabar) and Georgian. In 1914, he traveled to the South Caucasus to deliver lectures, recounted Gohar Mazmanyan, current director of the Tumanyan House Cultural Center and a philologist.

Tumanyan attended one of Bryusov’s lectures, met him in person, and invited him to their home. “There was frequent communication—Bryusov often visited Tbilisi with his wife,” said Mazmanyan. “During one of his visits to Tumanyan’s house, they agreed to select the best samples of Armenian literature—from the 5th century to the end of the 19th century—for translation into Russian and presentation in Moscow and St. Petersburg”.

Bryusov, along with notable Russian poets such as Blok, Bunin, Balmont, Akhmatova, and Sօlօgub, worked on translating these selected works. He would then bring the translations back to Tbilisi, where he and Tumanyan would review them together—checking the rhyme, language, and meaning for accuracy. “And in 1916, a remarkable book was published—a translated anthology of Armenian literary works,” Mazmanyan shared.

During the Soviet years, Hovhannes Tumanyan’s sons—well-educated and fluent in several languages—were persecuted and imprisoned, said Gohar Mazmanyan. His wife and other family members were evicted from the house and sent to Armenia. Only the family of his eldest son, Mushegh, remained in Tbilisi—his descendant is Elena.

“The building, confiscated from Iosif Shanshyan, was nationalized, and in 1953, part of Tumanyan’s home was allocated to Tbilisi’s Library No. 13. The other apartments of Shanshyan’s building were distributed among various families. After Georgia’s independence, the section of the building that housed Tumanyan’s home and the library was put up for sale. Passing from hand to hand, finally, with great difficulty, it was gradually purchased piece by piece and transferred to the Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Georgia,” said Gohar Mazmanyan, expressing gratitude to Armenian philanthropists Ruben Vardanyan and Vardan Ghukasyan, who bought the house and returned it to the Armenian community of Tbilisi.

On February 19, 2019, on the poet’s birthday, a memorial sculpture of Tumanyan—created by Davit Sirbiladze—was installed on the balcony. The sculpture was donated by Georgian Member of Parliament Davit Jijiashvili.

A Building of Memory: The Legacy and Secrets of Melik-Azaryants’ Palace in Tbilisi

On the sidewalk across from Rustaveli Metro Station, next to Georgia’s First Republic Square, stands a huge mansion with human sculptures and domed towers. This grand structure rises four to five stories high—with an additional four to five floors below ground.

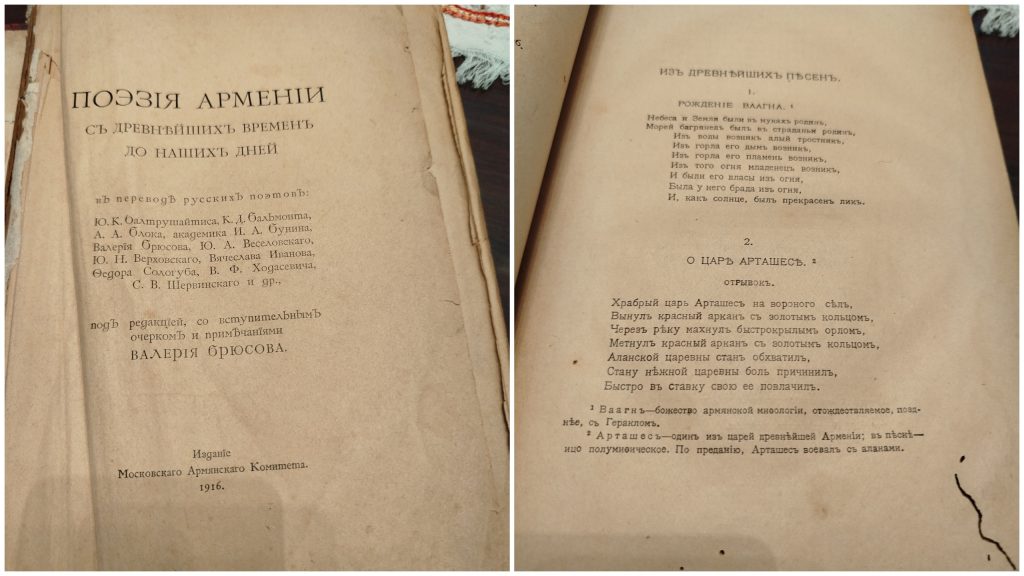

Art historian Inna Gyodakyan told it was built between 1912 and 1915 by Armenian philanthropist and wealthy businessman Alexander Melik-Azaryants, who was born in Tbilisi, lived and worked there, and eventually passed away in the city.

“Melik-Azaryants was an honorary member of the Armenian Philanthropic Society of the Caucasus and a member of the board of trustees of the Nersisian Seminary, the Armenian intellectual center in Tbilisi. He also owned oil fields in Baku, as well as built the first copper smelting plant and owned copper mines and stone mills in Armenia’s Syunik region”, Inna Gjodakyan said.

When constructing the Building on Rustaveli Avenue, Melik-Azaryants applied an innovative technology never before used in the Caucasus: a plumbum framework in the foundation. “It was probably his own idea,” said Inna, “since he was a geologist by profession.” This protected the structure from underground water and gave it exceptional strength.

Ekaterina Mikharidze, the columnist of the Sputnik Georgia, tells that in the 1970s, Georgian authorities wanted to demolish the building to expand the square. But after learning about the plumbum technology, they realized that the amount of explosives required would destroy not just the building—but the entire square.Built by Polish architect Nikolai Obolonsky, who lived in St. Petersburg, the mansion features somber tones, teardrop-shaped windows, and crowned stone carvings. When journalist Mikharidze wrote that the descendants of Melik-Azaryants were unknown, she was contacted by his great-granddaughter Natalia Kalantarova-Melik-Azaryants, who presented a collection of family documents preserved through generations—including ownership deeds for this and two other buildings in Tbilisi. On the metal window grilles of one of those houses—which Melik-Azaryants had gifted to the family of that great-granddaughter’s grandmother—the initials A and M, standing for Alexander Melik-Azaryants, are still visible.

Natalia is the granddaughter of Melik-Azaryants’ daughter, Sophia, who married a lawyer named Kalantarov and lived in this house, on Lermontov Street.

Natalia told the story why on Rustaveli street mansion’s somber colors are symbolic: a few years before its construction, Melik-Azaryants lost his 22-year-old daughter Taguhi to a severe illness, and he dedicated the house to her memory. Her death certificate is still preserved in the family. She is buried in Vera Cemetery, where Alexander Melik-Azaryants was also laid to rest later.

Inna Gjodakyan said the Rustaveli mansion was both a family residence and an income-generating property, with various apartments available for rent.

“This building is unique in another way,” explained the art historian. “It was the first in Tbilisi to have autonomous water and electricity systems. Water tanks were hidden in the domes. It had central heating, a telephone line, a cinema, a small garden with a fountain and exotic plants, and even a yardside for 24 carriages serving only the residents. The building also housed shops, a pharmacy, photo studios, a barber shop, and more.”

Just before the Bolsheviks came to power, Melik-Azaryants sent his wife and parents to France, said Inna. “He stayed behind in Tbilisi, waiting for a prospective buyer for the income property—an interested woman from France. However, upon witnessing the political instability, she changed her mind. Melik-Azaryants remained in Tbilisi, and when his home and assets were nationalized, he was allocated a small space in the basement of his former mansion. Once a wealthy merchant and prominent intellectual, he died in poverty in 1923”, Inna mentioned.

According to the beliefs of some of the contemporary renters of the areas in the house, which they shared with us, there is a curious spot in the basement of the Rustaveli mansion. “If you stand still, you can clearly hear tapping sounds—one of the many mysteries of this legendary house that have survived to our time”, they said.

Hidden Layers: The Armenian Legacy of Tbilisi

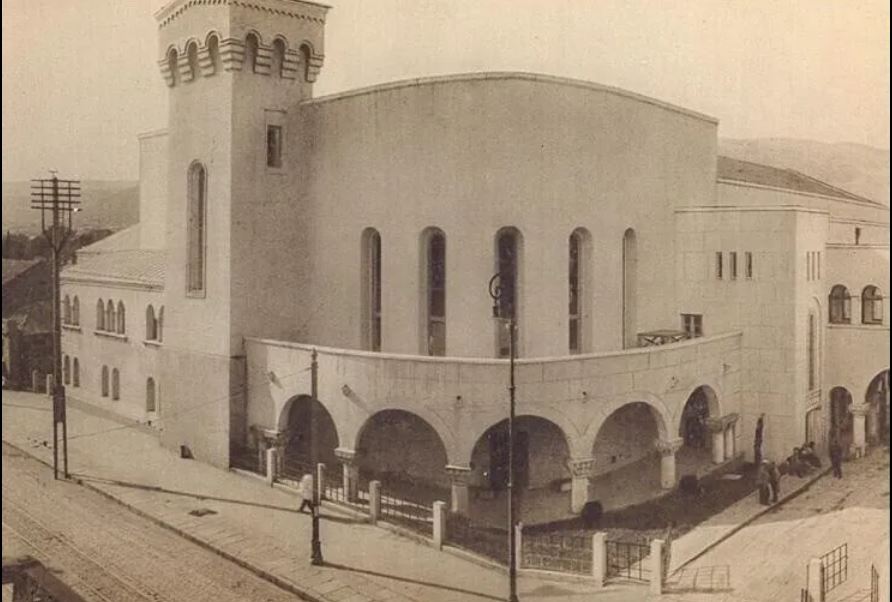

Russian nobleman and writer Mikhail Vladikin traveled throughout the Caucasus in the mid-19th century, collecting valuable information about the peoples living in Tbilisi at the time—their cultures, customs, occupations, and daily lives. He also studied statistical sources. As a result, he published his well-known documentary book titled “A Guide and Companion for Traveling in the Caucasus: With an Attached Railway Map.” Inna Gyodakyan cited testimonies from this book and declared that this book was officially published and republished at the state level and is currently available in the national libraries of both Georgia and Russia. She stated that this book provides first-hand information and serves as an equally, if not more, valuable source than, say, the testimony of a modern-day Georgian or Armenian journalists, historians, or any other cited authorities.

And in this book regarding Tbilisi, Vladikin writes: “Almost all trade in the South Caucasus was in Armenian hands. It may seem unbelievable, but it is absolutely accurate that in 1803, there were 2,700 houses in Tbilisi, only 4 of which belonged to Georgians and 15 to Georgian nobles—the rest were owned by Armenians. Thus, the capital of Georgia was entirely Armenian property.” (p. 330).

Inna Gyodakyan assured that at the time he wrote the book, Armenians still outnumbered other ethnic groups individually. She mentioned that Vladikin also notes–Armenians in Tbilisi were governed by their own Meliks (p. 328), and the title “Melik” was inherited in many Armenian noble families, from which surnames like Melikov derive—similar to how Georgian noble families bore titles like Eristavi.

As additional evidence, she cited a documentary book published in 1929 by the State Publishing House of Georgia, written by Professors Polievktov and Natadze, titled “Old Tiflis in the Accounts of Contemporaries”. In this book, they write: “The number of residents in Tiflis exceeds 20,000. Of the 2,000 houses in the city, almost all (no fewer than 1,800) belong to Armenians.” Finally, Inna Gyodakyan cited the Georgian historian, archaeologist, ethnographer, and corresponding member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, Dmitry Bakradze, who in his 1870 publication “Tiflis in Historical and Ethnographic Contexts” wrote: “The majority of the Buildings built in the European style owed their existence to the enterprise of the Armenians.”

The Armenian merchants Sumbatov’s, Bebutov’s, and Mirzoev’s sulfur baths were considered the oldest, she said, built in the first half of the 17th century. “In addition to these, according to 1916 records, the city also had baths owned by Tsovyanov, Tamamshev, Yedigaryan, Princes Abamelik and Argutinsky”.

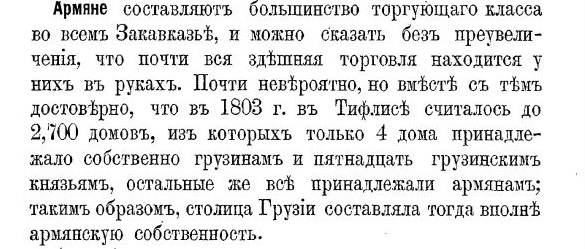

Adelkhanov built a leather and shoe factory in Ortachala, the art historian mentioned, Safarov and the Enfiandjian family established four tobacco factories, “Afrikyants built a multi-story underground and above-ground warehouse, Alikhanov financed the construction of the conservatory, and Aramyants built a hospital”.

Out of the seven bridges functioning before the revolution, art historian mentioned, two had “Armenian” origins – the Madatov Bridge, which connected the island of the same name to the right bank of the River, and the Mnatsakanov Bridge (located where the current 300 Aragvians), which he built for 25,000 rubles and donated to the city.

Inna Gyodakyan claimed that Armenian residential Buildings were primarily located in the city center. “On Golovin Avenue—now Rustaveli Avenue—were the homes of Mirimanov, Ter-Grigoryan, Ananov, Shahmuradyan, Artsruni, Sarajian, Onanov, and Rotinyants. On Erivan Square—now Liberty Square—stood the Buildings of Sumbatov, Kharazov, Ter-Asaturov, and Ishkhanov. In Sololaki lived the Seylanyan brothers, Tamamshev, Khambaryan, Khalatov, Shadinov, Akhverdyan, Amiraghov, Sharojev, Ghorganov, Alikhanov, Amntashev, Aramyants, Aghababov, Ionesyan, Pitoev, Gurgenov, Dolukhanov, Milov, Bozhardjyants, Ghalamkarov, Ghazarov, Bebutov, Yenikolopov, Tandoev, and others. Armenians also had private Buiildings on Mikhailov Avenue (now David Agmashenebeli Avenue), in Vera, and in Avlabari”, she said.

According to Inna, the largest Building before the revolution belonged to the famous Armenian magnate Alexander Mantashyants, at Ganovskaya 3/5—now Galaktion Street.

Inna Gyodakyan shared that this one and Mantashyants’ house on David Agmashenebeli Avenue were built by Armenian architect Gazaros Akopovich Sarkisyan, who, from 1917 to 1924, served as a professor at the Tbilisi Academy of Arts, teaching theoretical subjects and overseeing course and diploma projects at the faculty of architecture. “He mentored an entire generation of Georgian architects and designers and is considered one of the pioneers of the Art Nouveau style in Tbilisi”, she claimed.

The art historian also recounted the story of another mansion designed by the same architect, Gazaros Sarkisyan, the residence of Armenian merchant Mikhail Kalantarov (Kalantaryan). This Building Sarkisyan built in 1908, incorporating Moorish-style motifs.“There’s a popular rumor that a love story was tied to its construction. A wealthy merchant, the owner of one of Tbilisi’s horse-drawn tramway lines, fell in love with an opera singer. She replied to Mikhail’s courtship: ‘Build me a house more beautiful than our state theater—then maybe I’ll marry you.’ As we can see, the merchant kept his word. And the singer didn’t disappoint either. The couple had six children, and for each child, Mikhail planted a cypress tree in the inner courtyard—those six cypresses still stand there today,” said Inna Gyodakyan.

The same architect Sarkisyan also designed the Ananov House at 13 Griboedov Street–Tbilisi’s first building in modernist style, Mantashyants’ Trade School—now School No. 43 and commercial complex—the Mantashyants’ Trading Rows, she said.

After the establishment of the Soviet regime, architect Kazaros Sargsyan moved to Armenia and became one of the active contributors to the urban development of Gyumri, said Inna Gyodakyan.

Armenian architects such as Ohanjanov, Ter-Mikelov, Ter-Sarkisov, Zurabyan, Mikayelyan, Ter-Stepanov, Aghababyan, Akhverdov, Galumov, Lisianov, Madatov, Sarkisov, Khizanyan, Buzoghli, and others played a significant role in shaping the European face of Tbilisi.

Moreover, Inna Gyodakyan noted that Armenian architect Mikael Vardanovich Buzoghli—whose ancestors migrated to Georgia from Western Armenia, then under Ottoman rule—designed some of Georgia’s most prestigious resort areas and was among the first to design tea factories in the country. According to the art historian, he was the architect behind the curort zones in Menji and Tskaltubo, most of the recreation buildings in Borjomi and Bakhmaro as well as the tea factories in Chakvi and Zugdidi.

In Tbilisi, he also designed the building of Goskinprom (the Georgian State Film Studio) on David Agmashenebeli Avenue, nowadays the Georgian Studio for Documentary Films.

According to Inna Gyodakyan, Buzoghli taught at the Tbilisi Polytechnic Institute and the Institute of Railway Engineers. He was a member of the board of the Union of Architects of Georgia.

Art historian told, Armenian architect Pavel Alexandrovich Zurabyan served as the District Architect of the Tbilisi City Administration at 1899–1917, Chief Engineer of the Union of Georgian Cities at 1917–1919, and Chief Engineer of the Georgian Department of Resorts since 1920. He is the one who designed the Aramyants and Zubalov hospital pavilions (now the 1st City Hospital in Avlabari), the building of the Red Cross Hospital (Uznadze Street, now the Emergency Hospital), the Maternity Hospital building (Sovetskaya Street, long known as City Maternity Hospital No. 1), the Tbilisi branch of the Volga-Kama Bank (Ketskhoveli Street, now a branch of the National Library of Georgia).

He also designed over 30 large residential and income-generating Buildings in various parts of the city, said Inna. These Buildings reflected the eclectic style typical of the time.

Among the Buildings built at resorts, notable projects include the planning and construction of several facilities in the Shovi resort, Sanatorium Buildings “Arazindo” in Abastumani, rest houses “Chai-Georgia” and the former Zak.GPU in Gagra, the rest house “Pishchevkus” in Borjomi.

In Tbilisi, based on his architectural design and with funding from prominent Armenian philanthropists like Mantashyants and Aramyants, the building of the Nersisian Seminary was constructed using tuff stone brought from Armenia—today home to the Caucasus University, Inna told.

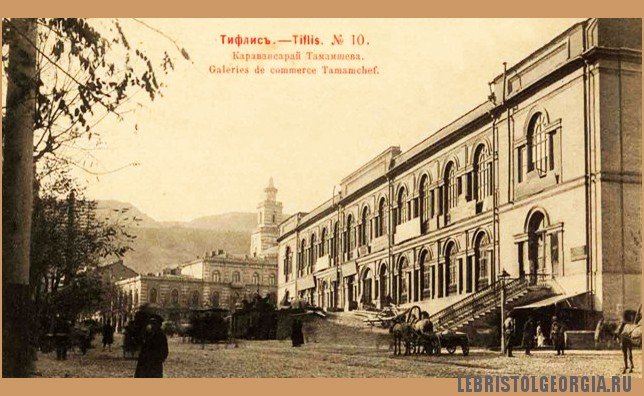

Back in 1847, on what was then Erivan Square (now Liberty Square), Tbilisi honorary citizen and wealthy Armenian Gabriel Tamamshev began construction of a remarkable building—the first opera theater in the Caucasus.

The Opera was designed by architect Giovanni Scudieri, told Inna Gyodakyan, and the interior was decorated by the famous Russian painter G. Gagarin. “Contemporaries were fascinated by the building and compared it to the Grand Opera in Paris”, she says, “But the theater functioned for only 23 seasons. On September 11, 1874, during a performance of Norma, it burned down and was never rebuilt”.

The same Tamamshev built the largest caravanserai in the city on the very same spot. It existed until 1934 and was demolished during the reconstruction of the square.

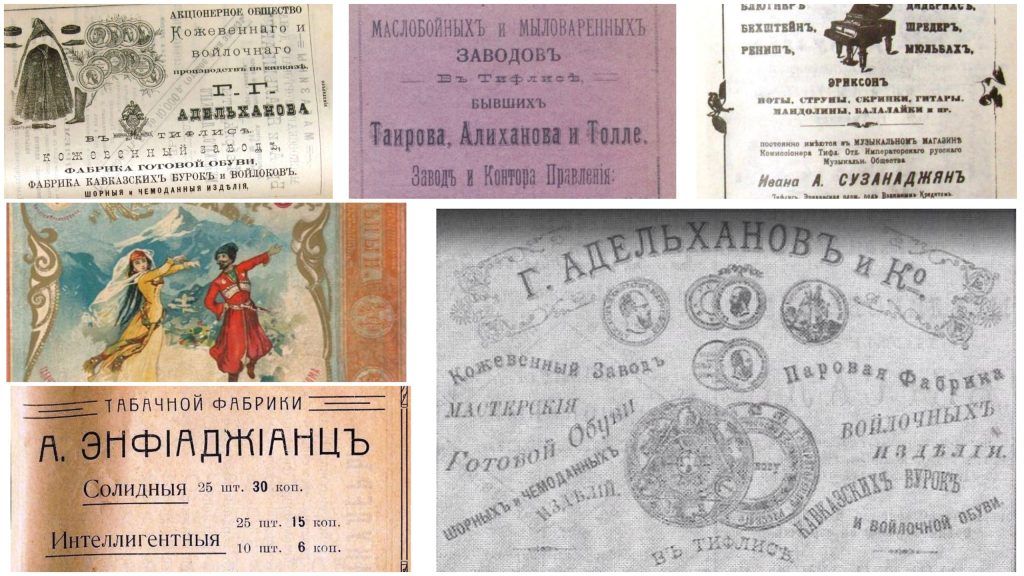

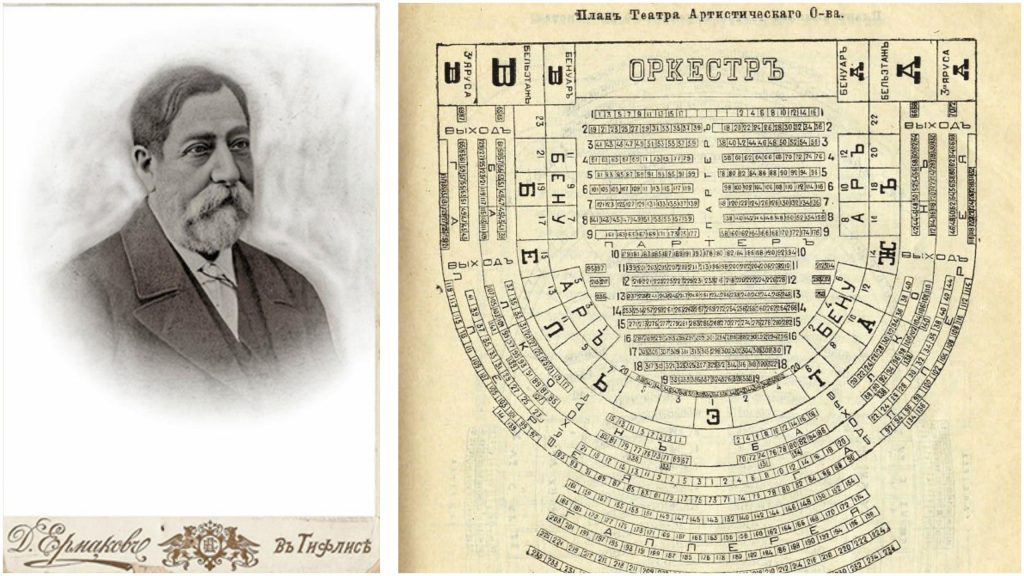

On February 6, 1901, the building of the “Artistic Society” was solemnly consecrated, Inna Gyodakyan said, it had been constructed with funds from the prominent Armenian merchant and philanthropist Isai Pitoev.

“The renowned entrepreneur and philanthropist was born in Tbilisi in 1844 in a family of the prominent Armenian businessman and industrialist, Egor Pitoev. The Pitoev family company was engaged in oil extraction and refining throughout the Caucasus, as well as sturgeon fishing and caviar production. After his father’s death, Isai became head of the family business, leading the company “Isai Egorovich Pitoev & Co.” There were five brothers in total and one sister, Margarita Egorovna. The children inherited noble status from their father”, art historian told the story of the family.

Isai Pitoev was known not only for his entrepreneurial ability but also for his deep and passionate love of the arts—especially theater, she told.

“Theater played such an important role in Pitoev’s life that he chose his wife from the theatrical world. Actress Olga Stanislavovna Marx, like her husband, was passionate about theater and served not only as his partner but as an ideological muse for his cultural endeavors. It all began with a small amateur theater troupe, which the Pitoevs organized in their home on Paskevich Street. The performances quickly gained popularity, and the group was soon transformed into the “Artistic Society.” The brothers gathered a talented ensemble. Under their initiative, famous artists such as actress Vera Komissarzhevskaya, singer Fyodor Chaliapin, and composers Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov and Pyotr Tchaikovsky visited Tbilisi. As their theatrical activities expanded, their home could no longer accommodate the growing audience”, Inna Gyodakyan said.

It was then, she told, that Isai Pitoev realized his long-held dream—he began constructing a theater on Golovin Avenue (now Rustaveli Avenue).

“He purchased a plot from the city authorities—previously the site of a Muslim cemetery—and brought in renowned architects Korneliy Tatishchev and Alexander Shimkevich to design the building. Within just three years, construction was completed on a magnificent example of Late Baroque architecture. The Artistic Society opened its new home in 1901. Pitoev spent 1.5 million rubles to build this theater, which would later host Armenian, Georgian, and Russian theater troupes on its stage”, Inna told.

Isai Pitoev had many more grand plans for the theater–Inna said–but they were not meant to be. He passed away in 1904. Following the Bolshevik rise to power, the Pitoev family emigrated to Europe. In 1921, the theater was renamed the State Drama Theatre after Shota Rustaveli.

Inna Gyodakyan told, these stories gave her boundless energy and make her love Tbilisi even more. Gyumri, where she lives, is only 200 kilometers away from Tbilisi. Every time she comes to this city, she feels like she’s visiting a close relative—overwhelmed with warmth and affection, not only toward the city itself, but also toward its people, who, despite the hardships of history, have lovingly preserved the legacy of the city’s rich heritage and high culture through the generations.

By Anna Balyan